Ice Milling

with

Jussi Ängeslevä

Pinnannousu

Jussi Angeslevä

Project Intention

The project draws on research conducted between 2016 and 2018 by the Berlin University of the Arts (Jussi Ängeslevä), the University of Lapland (Ismo Alakärppä), and EPFL (Mark Pauly). This research, part of the DIARWE project, explored methods for creating caustic lenses from natural ice that refract sunlight to form arbitrary images.

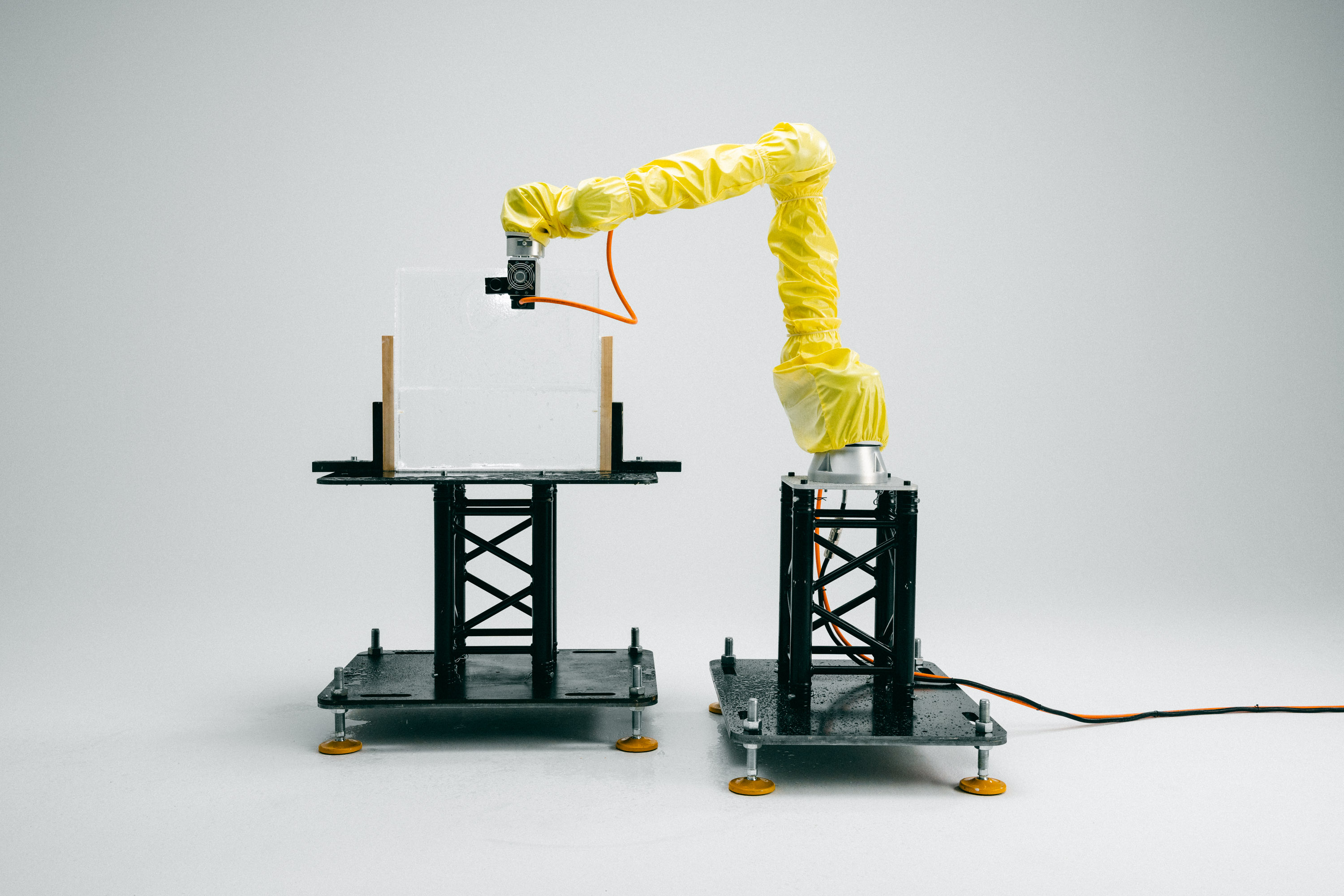

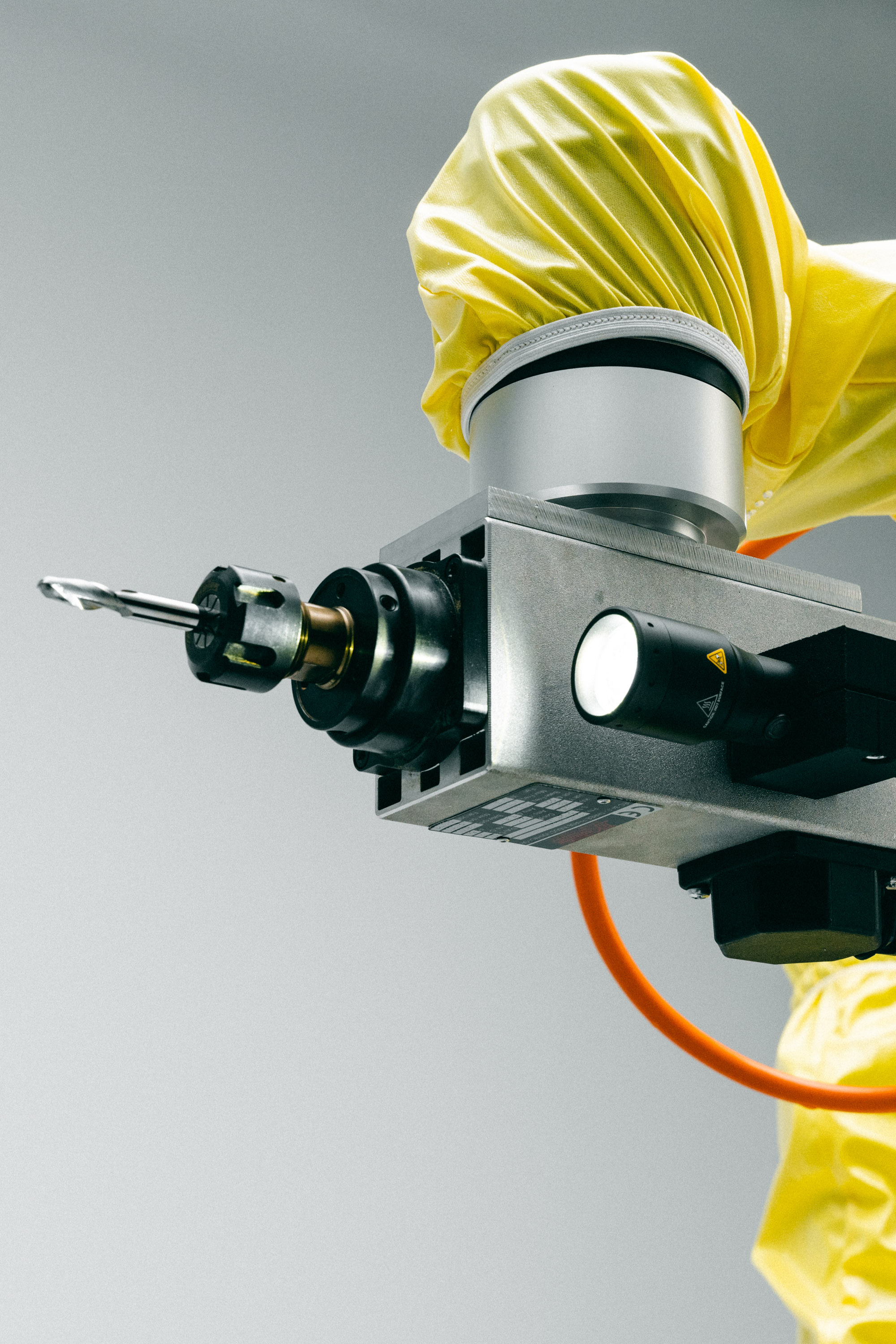

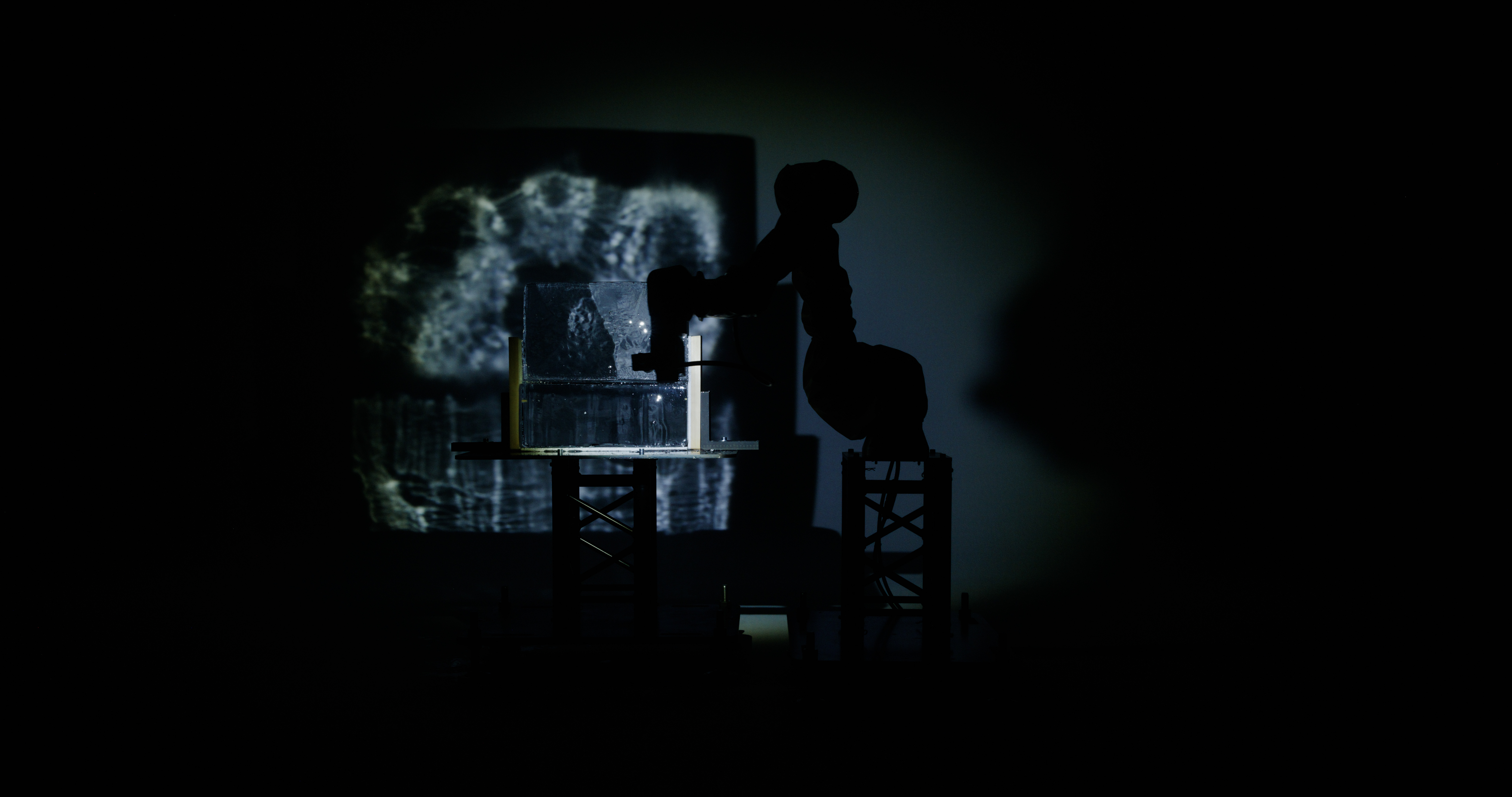

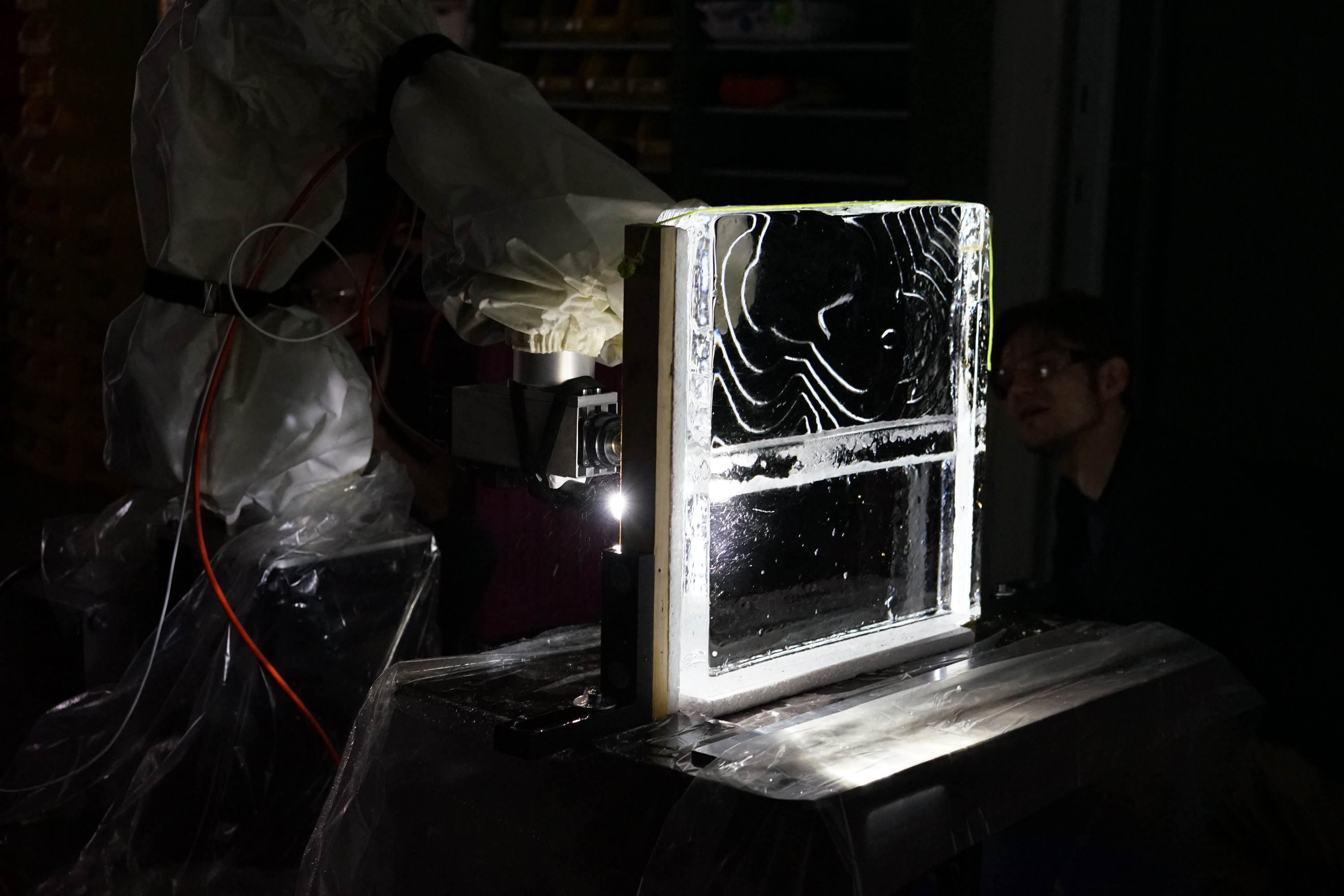

The artwork consists of three elements—a block of ice being carved by a drill attached to a robotic arm, another block of ice already carved and melting, and a screen with a projected movie of the melting process captured with a time-lapse camera. The ice block carved by the robotic arm is gradually converted into a caustic lens, which refracts the light from a flashlight attached to the arm and projects an image onto the wall. Processing the slowly melting ice block into a computed lens shape is an attempt to give form to something that has no defined shape and reminds us of the human act of trying to somehow stop global challenges that know no bounds.

Sapporo International Art festival theme in 2024 is “Last Snow”, contemplating on the northern dimension in the way we see humanity as part of changing nature. As a part of the festival, Pinnannousu is installed in the snow storage chamber for the cooling system at Moerenuma Park’s Glass Pyramid.

Technical Breakdown

Invited Artist/Designer

Jussi Ängeslevä

Project Title

Pinnannousu

Tools

UR10, CNC Spindle, Torch light

Medium

Ice, Rays of light

Software

Autodesk Fusion360, Custom Software from Rayform to calculate Mesh for the caustic image.

Technique used

Toolpath generation using Autodesk Fusion360 and Gcode Post-processor. The Gcode is then run via Remote TCP and Toolpath URCap.

The geometry that has been milled into the ice block has been generated using the technology developed by Rayform, allowing to transform a 2D image into a mesh that creates the caustic image when illuminated with a light source. In order to mill the ice block a toolpath has been generated using Autodesk Fusion360. The toolpath has been exported as Gcode with the built-in post-processor. The Gcode is then run via Remote TCP and Toolpath URCap.

The UR10 is equipped with a powerful milling spindle, constantly turning. The ice block used is made of high-quality ice, free from any imperfections or air bubbles. This type of ice is typically produced for ice sculpting.

Jussi Ängeslevä

Professor Jussi Ängeslevä is a designer, an artist and an educator. Having taught at the Berlin University of the Arts and Royal College of Arts in London, he is working with digital materiality and interaction design. His work as Creative Director at ART+COM Studios commands global recognition in media arts and exhibition design. His focus is in between fields: combining understanding of visual, physical and interaction design with algorithmic, electronic and mechatronic knowledge to create innovative and elegant experiences, where the meaning is inseparable from the medium communicating it. He now lives and works in Palo Alto, California, United States.

Reflexion on the process: in discussion with Jonas Berthod

What was the idea you originally brought to “A Third Hand”?

I wanted to use a robotic arm to carve a block of ice to a computed geometry form in order to transform it into a caustic lens, one where shining light through the block would converge to a legible image. A robot milling a block of ice is spectacular, full of symbolic meaning. With this performance-like act of making, which works against the continuous process of melting, I wanted to find a balance between the performative and the aspect of “digital fabrication”.

I had been working on caustic lenses with EPFL’s Mark Pauly before, so I had quite a good understanding of the possibilities. However, working with a robotic arm, its general applicability, and the countless details concerning how to optimize, how to configure, and how to best estimate the right dimensions and ways of working were all beyond the scope of my knowledge. Hence, having roboticist experts with a strong propensity of artistic expression was a perfect opportunity to work on this together.

What steps did you take?

Since I had been working with computational caustics before, I spent time reflecting on what I had done previously, and what kind of visual world, physical dimensions and dynamic movements might be the most appropriate to explore as part of this project. With 3D renderings and sample files, I was then able to prepare for the actual workshop visit in Switzerland to best gain the knowledge and experience for the final work. From the conversations in the early part of the project, with AATB as well as with EPFL, we had a great basis to prepare for the workshop visit optimally. With the concept clear in everyone’s mind, we could analyse and discuss the challenges and potentially interesting aspects well in advance, so that during the workshop visit we were able to iterate and execute the various tests to gain new knowledge.

In this case, the previous experiments I had done on other projects, and the team that I knew already partially, complemented the new connection to AATB and their special expertise.

In what ways does your project benefit from the involvement of a robotic arm, and in what fields do you see potential for artistic exploration?

In my daily work at ART+COM and at Universität der Künste Berlin, I always strive for hands on, iterative working “with the medium”. It is so easy to end up in a speculation loop where countless abstract models, computer visualisations and simulations lead the process towards an idealised world that does not correspond with reality. In that case, once faced with the final realisation, the work ends up being all about “fighting against” the innate properties of the system. I much prefer working with robotic arms – instead of thinking about what robotic arms might do – which renders the process smooth. AATB’s expertise made the practical work extremely easy: I benefited from our conversations on what is important, where the interesting angles might be, whilst keeping in mind what the machines are meant for and how to operate them safely. Very often, when I am confronted with new technology, the early stages can be somewhat precarious experiments, and this is an often dangerous and less optimized process. The combination of access to hardware and to people with lot of experience with the hardware, but also in similar mindset about the qualities they provide in the context of artistic expression (instead of talking with engineers with no interest in the arts) was excellent.

Which parts of the project did not go as planned and how did you adapt?

We realised that the actual milling ended up not being particularly spectacular, because the robot’s movement when machining the surface is not very dramatic. However, the robot carries a flashlight which ends up being so close to the ice block that the resulting caustic reflections created a beautiful, immersive projection on the walls. This made the presence of the audience in the light suddenly a core component of the project.

We also started looking at how we might integrate more expressive gestures with the robot as a kind of interlude where the milling process is stopped and the robot is “looking at” the block of ice, as if to reflect what to do next. We experimented with a manual process whereby we programmed the robot by moving it by hand to different target locations and interpolating between them. This hands-on movement blended with the pre-computed high precision milling was a beautiful addition to the core concept.

On the other hand, which parts went well, and were you able to push the research further than expected thanks to these favourable outcomes?

Most certainly! As explained above, after we saw how the milling process transformed the space, we were able to iterate quickly on how this might become an elegant part of a performance. As a result, we now have a solid, thought-through plan for the final installation that is not too heavy on technology, but also includes human expression.

Which parts of the process brought surprise, delight, joy or unexpected success?

The tight loop of the process was full of surprises and discoveries of aesthetic possibilities. Having a hypothesis, preparing material for it, trying it out, seeing the result, reflecting with the experts on the implications, and quickly running different experiments to validate, explore and document the different possibilities was a delight.

How will your project contribute to the potential uses of a robotic arm by designers and artists? How do you hope others will be able to benefit from your research, and what do you hope they will do with it?

I think that robotic artworks often have a clearly defined role for the robot and its performance is then often evaluated in relation to the “optimal” performance of what one might expect. I hope that this project in which the predefined process, the computational precision of the machine, is now combined with performative programming – the artist literally dancing with the robot arm, in order to program the tool path for optimal shadow play – is suddenly treating the robot in a different function and expands its role as a part of the project.

In addition, digital fabrication is often framed so that the resulting output is at the centre of the attention. In this case, the continuous melting process, the milling whilst melting and the resulting speeded-up melting all turn the focus on the process, and not the outcome.

Finally, the outcome mixes aleatory reflections, the shadows cast by the audience and the inhumane, perfectly robotic movement. This makes things immersive and interactive, without the visitors having to press any buttons, wiggle any joysticks, wave hands, make sounds or send commands through mobile phones. Interaction happens in the material world, and not just in the digital.

Will your involvement in the project have an impact on your own practice? How and why?

I have been working for a long time in a tightly knit team. This has the advantage of knowing what the team members are good at, what drives them, and how to communicate with them. I recently moved to a different continent, and this project enabled me more eye level collaboration with other teams, which was an excellent shift of perspective. It makes it possible for me to keep working in the technological avantgarde without having an established studio where everything needs to happen under one roof.